- Joined

- Jan 25, 2014

- Messages

- 11,992

- Reaction score

- 1,413

- Points

- 159

Why The Word Homosexual Is Offensive

TheWeek | By Nicholas Subtirelu | June 2 2015

SOURCE

TheWeek | By Nicholas Subtirelu | June 2 2015

If you're a member of a stigmatized group, such as a person of color or a gay man or woman, even the smallest of talk can be fraught with small discomforts, slights, and aggressions.

Such casual offenses need not be intentional. Indeed, they often aren't.

For example, consider the word "homosexual," which Jeremy Peters writes "probably sounds inoffensive" to most people. I am a straight man who considers myself to be politically aligned with the struggles of gay men and women, and I frequently use the term (including just last night). I was surprised then to learn that the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) listed it as an offensive term back in 2006.

I thought it was strange that I was so oblivious, so I began researching. I emerged with a couple of explanations about the term's offensiveness.

First, people often point to parts of the word itself to explain its offensiveness. They point out that, since it includes "sexual," the word focuses on sexual acts and not on gay men and women's basic humanity or that the word is related to a recognizable slur, "homo."

Second, some have also looked at the word's history and pointed out that "homosexual" has a history of being used to pathologize gays and lesbians. For example, the American Psychological Association considered homosexuality a psychological disorder until 1973.

These explanations are compelling, but I'm not sure they tell the whole story. For example, if the inclusion of "sexual" is the problem with "homosexual," why do I not feel equally uncomfortable with "heterosexual"?

Also, if similarity to a slur is such a problem, then why is the preferred term "gay"? After all, "gay" is often used cruelly, like when it's used to mean lame or stupid. Finally, as a linguist, I know that historical usage, while usually very interesting, often has very little relevance to how words are used and understood contemporaneously.

This led me to take a look at the use of "homosexual" by politicians, specifically members of the U.S. Congress, through data made available on CapitolWords.org by the Sunlight Foundation. It proved illuminating.

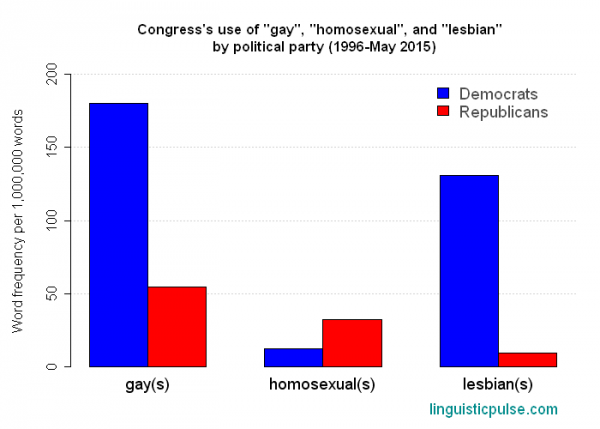

I was specifically interested in how different labels for gay men and women are used by Congressional Democrats and the Republicans, who have historically taken different stances on issues of deep concern to many gay men and women such as employment discrimination. The data I collected shows interesting tendencies in the use of "gay," "homosexual," and "lesbian" by political party.

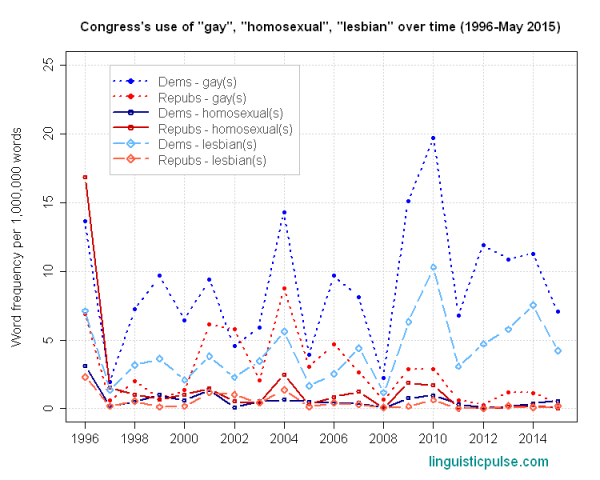

For Democrats, "gay" and "lesbian" are both preferred over "homosexual." Republicans also prefer "gay" over "homosexual" but rarely use "lesbian." However, Republicans' preference for "gay" is far weaker, and they use the word "homosexual" more than Democrats do. In addition, Republicans have not always avoided the word "homosexual," as the graph below makes clear.

In this data, 1996 is the peak year for use of the word "homosexual." (It was also the first year digitized data is available, so we don't know if usage in 1995, much less 1955, was even higher.)

Republicans used the term quite frequently in 1996 as Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which excluded same sex unions from the federal government's definition of marriage, and the Senate debated, but did not pass, the Employment Nondiscrimation Act of 1996 (ENDA), which would have given legal protections to gays and lesbians in the workplace.

The divide between Democrats and Republicans was somewhat murky in 1996, both in terms of word usage and support for causes important to gays and lesbians. In fact, a majority of both Republicans and Democrats voted in favor of DOMA. However, it was mostly the Republicans in the Senate who opposed ENDA, and this opposition was accompanied by frequent use of the word "homosexual," such as when Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) asked rhetorically, "Should the Senate run roughshod over the concerns of parents and educators about having homosexuals teach their kids?"

An even stronger divide emerged several years later when the House voted on an extension of DOMA, the Marriage Protection Act of 2004 (which died in the Senate). The vast majority of Republicans supported the bill, and the vast majority of Democrats opposed it, although in this year Republicans' use of "homosexual" was far more limited.

In its history of use in Congress, the word "homosexual" has largely been associated with some of the most clearly anti-gay politicians like Steve King (R-Iowa) and Louie Gohmert (R-Texas). Interestingly, the term has also been frequently used by former Democratic congressman Barney Frank, who is himself gay, although Frank is also a frequent user of "gay."

In the end, "homosexual" has largely faded out of use in Congress in the past few years, but so it seems has Republican discussion of gay men and women.

The offense that some gay men and women take to the term "homosexual" can be explained in part by its association with anti-gay stances heard especially in the 1990s and 2000s, not only in Congress but also on talk radio, at church, and around the dinner table. The subtle but close association between anti-gay politics and the term "homosexual" means that when they hear "homosexual" some gays and lesbians hear opposition to their struggle for equal treatment under the law and homophobic conspiracy theories about immoral and corrupt "homosexual agendas." It's no wonder they're offended.

SOURCE

Last edited:

stances. As I said before, you can classify a single sexual encounter between two people as either homosexual or heterosexual. But that's where the certainty ends. Once you look at all of a person's life and experience, two boxes are not enough. So sexual orientation is even problematic as an attribute because there is no objective way to sort out one from the other.

stances. As I said before, you can classify a single sexual encounter between two people as either homosexual or heterosexual. But that's where the certainty ends. Once you look at all of a person's life and experience, two boxes are not enough. So sexual orientation is even problematic as an attribute because there is no objective way to sort out one from the other.