- Joined

- Jan 25, 2014

- Messages

- 12,016

- Reaction score

- 1,564

- Points

- 159

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (/ˈpjɔːtər iːˈljiːtʃ tʃaɪˈkɒfski/; Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский;tr. Pyotr Ilyich Chaykovsky; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893), often anglicised as Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky /ˈpiːtər .../, was a Russian composer whose works included symphonies, concertos, operas, ballets, chamber music, and a choral setting of the Russian Orthodox Divine Liturgy. Some of these are among the most popular theatrical music in the classical repertoire. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally, which he bolstered with appearances as a guest conductor later in his career in Europe and the United States. One of these appearances was at the inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall in New York City in 1891. Tchaikovsky was honored in 1884 by Emperor Alexander III, and awarded a lifetime pension in the late 1880s.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant. There was scant opportunity for a musical career in Russia at that time, and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five, with whom his professional relationship was mixed. Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From this reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style—a task that did not prove easy. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music; this seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or from forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great, and this resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia of the country's national identity.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his leaving his mother for boarding school, his mother's early death, as well as that of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein, and the collapse of the one enduring relationship of his adult life, his 13-year association with the wealthy widow Nadezhda von Meck. His homosexuality, which he kept private, has traditionally also been considered a major factor, though some musicologists now downplay its importance. His sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera; there is an ongoing debate as to whether it was accidental or self-inflicted.

While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it was sufficiently representative of native musical values and were suspicious that Europeans accepted it for its Western elements. In apparent reinforcement of the latter claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than base exoticism, and thus transcending stereotypes of Russian classical music. Tchaikovsky's music was dismissed as "lacking in elevated thought," according to longtime New York Times music critic Harold C. Schonberg, and its formal workings were derided as deficient for not following Western principles stringently.

Childhood trauma and school years

A row of large, stone three-story buildings alongside a large riverbank.

Modern view of the Imperial School of Jurisprudence

Tchaikovsky's separation from his mother to attend boarding school caused an emotional trauma that tormented him throughout his life. Her death from cholera in 1854 further devastated him, affecting him so much that he could not inform Fanny Dürbach until two years later. He mourned his mother's loss for the rest of his life and called it "the crucial event" that ultimately shaped it. More than 25 years after his loss, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, "Every moment of that appalling day is as vivid to me as though it were yesterday." The loss also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky's father, who also contracted cholera at this time but fully recovered, immediately sent him back to school, hoping that classwork would occupy the boy's mind. In partial compensation for his isolation and loss, Tchaikovsky made lifelong friendships with fellow students, including Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard. Music became a unifier. While it was not an official priority at the School of Jurisprudence, Tchaikovsky maintained an extracurricular connection by regularly attending the opera with other students. Fond of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi and Mozart, he would improvise for his friends at the school's harmonium on themes they had sung during choir practice. "We were amused," Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory." Tchaikovsky also continued his piano studies through Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who made occasional visits to the school; however, the results, according to musicologist David Brown, were "negligible".

Emotional life

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to same-sex attraction and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at armchair analysis by Western biographers. A current tendency is to discuss Tchaikovsky's personal life candidly.

Tchaikovsky lived as a bachelor most of his life. In 1877, at the age of 37, he wed a former student, Antonina Miliukova. The marriage was a disaster. Mismatched psychologically and sexually, the couple lived together for only two and a half months before Tchaikovsky left, overwrought emotionally and suffering from an acute writer's block. Tchaikovsky's family remained supportive of him during this crisis and throughout his life. He was also aided by Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway magnate who had begun contact with him not long before the marriage. As well as an important friend and emotional support, she also became his patroness for the next 13 years, which allowed him to focus exclusively on composition.

Sexuality

Tchaikovsky had clear homosexual tendencies and some of the composer's closest relationships were with men. He sought out the company of other same-sex attracted men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them." Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's sexual orientation, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it.

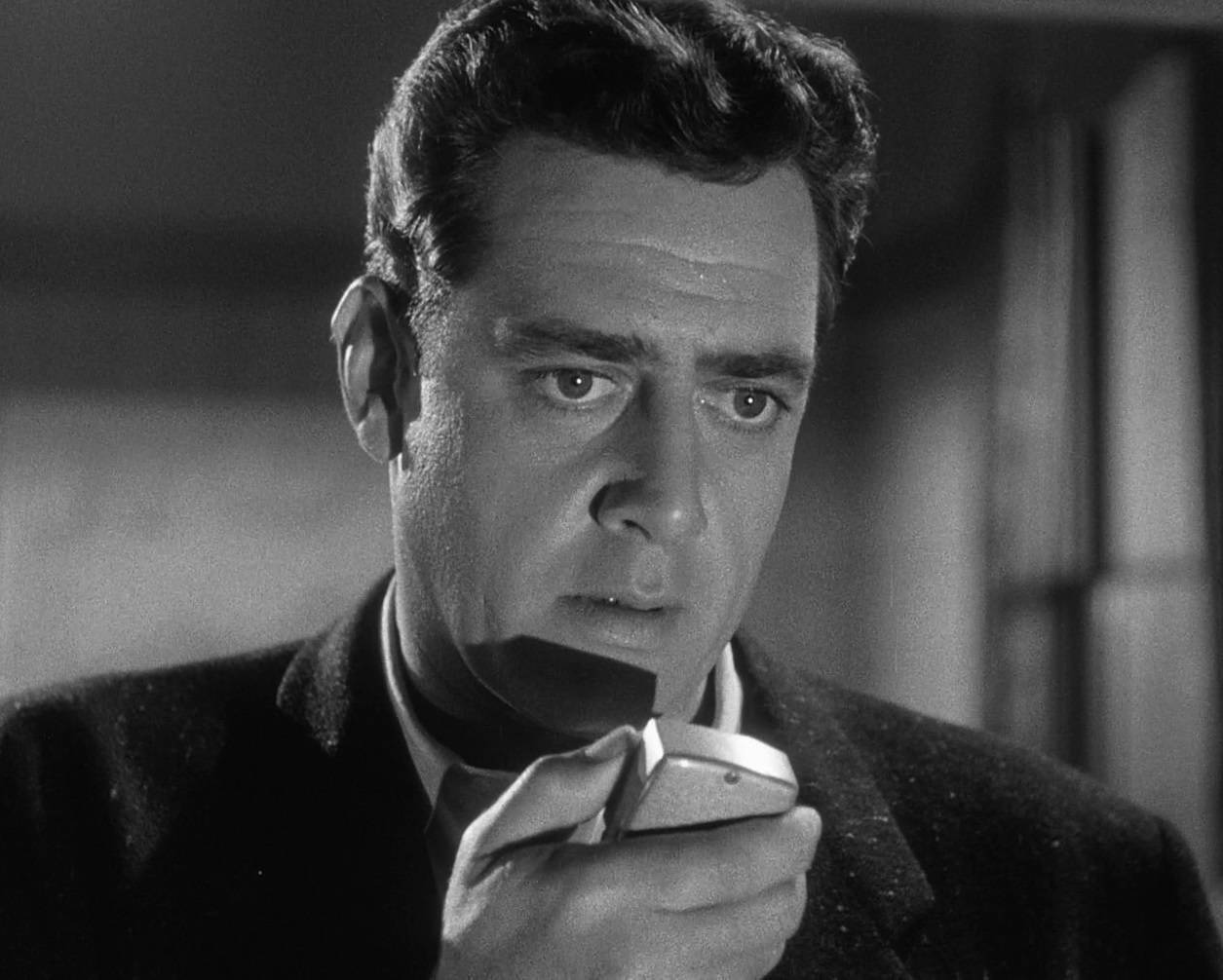

Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky

More debatable is how comfortable the composer felt with his sexual nature. There are currently two schools of thought. Musicologists such as David Brown have maintained that Tchaikovsky "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape." Another group of scholars, which includes Alexander Poznansky and Roland John Wiley, have more recently suggested that the composer experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual nature and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage."

Both groups agree that Tchaikovsky remained aware of the negative consequences should knowledge of his orientation become public, especially of the ramifications for his family. While his father continued to hope Tchaikovsky would marry (and may have been unaware of his son's orientation), other members of his loving and supportive family remained more open-minded. Modest shared his sexual orientation and became his literary collaborator, biographer and closest confidant. Tchaikovsky was eventually surrounded by an adoring group of male relatives and friends, which may have aided him in achieving some sort of psychological balance and inner acceptance of his sexual nature.

The level of official tolerance Tchaikovsky may have experienced, which could fluctuate depending on the broad-mindedness of the ruling Tsar, is also open to question. One argument is that general intolerance of same-sex orientation was the rule in 19th century Russia, punishable by imprisonment, loss of all rights, banishment to the provinces or exile from Russia altogether; therefore, Tchaikovsky's fear of social rejection was grounded in some justification. Musicologist Solomon Volkov mentions state do ents that indicate men attracted to the same sex "were under tight police surveillance" and maintains that public life in Russia was "based not on laws but on 'understandings.' That means that formally existing laws are applied or ignored based on the position and wishes of the authorities.... No one could feel confident of the future in those conditions (which is one of the goals of a society built on 'understandings')." The other argument is that the Imperial bureaucracy was considerably less draconian in Tchaikovsky's lifetime than previously imagined. Russian society, with its surface veneer of Victorian propriety, may have been no less tolerant than the government. In the introduction to a French edition of her biography of Tchaikovsky (first published in Russian in 1936 and reissued in French in 1987) Nina Berberova cites many cir

ents that indicate men attracted to the same sex "were under tight police surveillance" and maintains that public life in Russia was "based not on laws but on 'understandings.' That means that formally existing laws are applied or ignored based on the position and wishes of the authorities.... No one could feel confident of the future in those conditions (which is one of the goals of a society built on 'understandings')." The other argument is that the Imperial bureaucracy was considerably less draconian in Tchaikovsky's lifetime than previously imagined. Russian society, with its surface veneer of Victorian propriety, may have been no less tolerant than the government. In the introduction to a French edition of her biography of Tchaikovsky (first published in Russian in 1936 and reissued in French in 1987) Nina Berberova cites many cir stances that confirm social visibility and impunity of homosexual men in 1890s Russia.

stances that confirm social visibility and impunity of homosexual men in 1890s Russia.

In any case, Tchaikovsky chose not to neglect social convention and stayed conservative by nature. His love life remained complicated. A combination of upbringing, timidity and deep commitment to relatives precluded his living openly with a male lover. A similar blend of personal inclination and period decorum kept him from having sexual relations with those in his social circle. He regularly sought out anonymous encounters, many of which he reported to Modest; at times, these brought feelings of remorse. He also attempted to be discreet and adjust his tastes to the conventions of Russian society. Nevertheless, many of his colleagues, especially those closest to him, may have either known or guessed his true sexual nature. Tchaikovsky's decision to enter into a heterosexual union and try to lead a double life was prompted by several factors—the possibility of exposure, the willingness to please his father, his own desire for a permanent home and his love of children and family. There is no reason however to suppose that these personal travails impacted negatively on the quality of his musical inspiration or capacity. An upcoming Russian film, Tchaikovsky, has attracted controversy due to the fact that Tchaikovsky's sexuality, mentioned in early drafts, has been written out of the film in order to secure funding from the Russian government.

Death

On 28 October 1893 Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique In Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died there, aged 53. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, and Modest Mussorgsky; later, Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev were also buried nearby.

While Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier, some have theorized that his death was a suicide. Opinion has been summarized as follows: "The polemics over [Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumor attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out ....."

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (/ˈpjɔːtər iːˈljiːtʃ tʃaɪˈkɒfski/; Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский;tr. Pyotr Ilyich Chaykovsky; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893), often anglicised as Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky /ˈpiːtər .../, was a Russian composer whose works included symphonies, concertos, operas, ballets, chamber music, and a choral setting of the Russian Orthodox Divine Liturgy. Some of these are among the most popular theatrical music in the classical repertoire. He was the first Russian composer whose music made a lasting impression internationally, which he bolstered with appearances as a guest conductor later in his career in Europe and the United States. One of these appearances was at the inaugural concert of Carnegie Hall in New York City in 1891. Tchaikovsky was honored in 1884 by Emperor Alexander III, and awarded a lifetime pension in the late 1880s.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant. There was scant opportunity for a musical career in Russia at that time, and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five, with whom his professional relationship was mixed. Tchaikovsky's training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From this reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style—a task that did not prove easy. The principles that governed melody, harmony and other fundamentals of Russian music ran completely counter to those that governed Western European music; this seemed to defeat the potential for using Russian music in large-scale Western composition or from forming a composite style, and it caused personal antipathies that dented Tchaikovsky's self-confidence. Russian culture exhibited a split personality, with its native and adopted elements having drifted apart increasingly since the time of Peter the Great, and this resulted in uncertainty among the intelligentsia of the country's national identity.

Despite his many popular successes, Tchaikovsky's life was punctuated by personal crises and depression. Contributory factors included his leaving his mother for boarding school, his mother's early death, as well as that of his close friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein, and the collapse of the one enduring relationship of his adult life, his 13-year association with the wealthy widow Nadezhda von Meck. His homosexuality, which he kept private, has traditionally also been considered a major factor, though some musicologists now downplay its importance. His sudden death at the age of 53 is generally ascribed to cholera; there is an ongoing debate as to whether it was accidental or self-inflicted.

While his music has remained popular among audiences, critical opinions were initially mixed. Some Russians did not feel it was sufficiently representative of native musical values and were suspicious that Europeans accepted it for its Western elements. In apparent reinforcement of the latter claim, some Europeans lauded Tchaikovsky for offering music more substantive than base exoticism, and thus transcending stereotypes of Russian classical music. Tchaikovsky's music was dismissed as "lacking in elevated thought," according to longtime New York Times music critic Harold C. Schonberg, and its formal workings were derided as deficient for not following Western principles stringently.

Childhood trauma and school years

A row of large, stone three-story buildings alongside a large riverbank.

Modern view of the Imperial School of Jurisprudence

Tchaikovsky's separation from his mother to attend boarding school caused an emotional trauma that tormented him throughout his life. Her death from cholera in 1854 further devastated him, affecting him so much that he could not inform Fanny Dürbach until two years later. He mourned his mother's loss for the rest of his life and called it "the crucial event" that ultimately shaped it. More than 25 years after his loss, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, "Every moment of that appalling day is as vivid to me as though it were yesterday." The loss also prompted Tchaikovsky to make his first serious attempt at composition, a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky's father, who also contracted cholera at this time but fully recovered, immediately sent him back to school, hoping that classwork would occupy the boy's mind. In partial compensation for his isolation and loss, Tchaikovsky made lifelong friendships with fellow students, including Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard. Music became a unifier. While it was not an official priority at the School of Jurisprudence, Tchaikovsky maintained an extracurricular connection by regularly attending the opera with other students. Fond of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi and Mozart, he would improvise for his friends at the school's harmonium on themes they had sung during choir practice. "We were amused," Vladimir Gerard later remembered, "but not imbued with any expectations of his future glory." Tchaikovsky also continued his piano studies through Franz Becker, an instrument manufacturer who made occasional visits to the school; however, the results, according to musicologist David Brown, were "negligible".

Emotional life

Discussion of Tchaikovsky's personal life, especially his sexuality, has perhaps been the most extensive of any composer in the 19th century and certainly of any Russian composer of his time. It has also at times caused considerable confusion, from Soviet efforts to expunge all references to same-sex attraction and portray him as a heterosexual, to efforts at armchair analysis by Western biographers. A current tendency is to discuss Tchaikovsky's personal life candidly.

Tchaikovsky lived as a bachelor most of his life. In 1877, at the age of 37, he wed a former student, Antonina Miliukova. The marriage was a disaster. Mismatched psychologically and sexually, the couple lived together for only two and a half months before Tchaikovsky left, overwrought emotionally and suffering from an acute writer's block. Tchaikovsky's family remained supportive of him during this crisis and throughout his life. He was also aided by Nadezhda von Meck, the widow of a railway magnate who had begun contact with him not long before the marriage. As well as an important friend and emotional support, she also became his patroness for the next 13 years, which allowed him to focus exclusively on composition.

Sexuality

Tchaikovsky had clear homosexual tendencies and some of the composer's closest relationships were with men. He sought out the company of other same-sex attracted men in his circle for extended periods, "associating openly and establishing professional connections with them." Relevant portions of his brother Modest's autobiography, where he tells of the composer's sexual orientation, have been published, as have letters previously suppressed by Soviet censors in which Tchaikovsky openly writes of it.

Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky

More debatable is how comfortable the composer felt with his sexual nature. There are currently two schools of thought. Musicologists such as David Brown have maintained that Tchaikovsky "felt tainted within himself, defiled by something from which he finally realized he could never escape." Another group of scholars, which includes Alexander Poznansky and Roland John Wiley, have more recently suggested that the composer experienced "no unbearable guilt" over his sexual nature and "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage."

Both groups agree that Tchaikovsky remained aware of the negative consequences should knowledge of his orientation become public, especially of the ramifications for his family. While his father continued to hope Tchaikovsky would marry (and may have been unaware of his son's orientation), other members of his loving and supportive family remained more open-minded. Modest shared his sexual orientation and became his literary collaborator, biographer and closest confidant. Tchaikovsky was eventually surrounded by an adoring group of male relatives and friends, which may have aided him in achieving some sort of psychological balance and inner acceptance of his sexual nature.

The level of official tolerance Tchaikovsky may have experienced, which could fluctuate depending on the broad-mindedness of the ruling Tsar, is also open to question. One argument is that general intolerance of same-sex orientation was the rule in 19th century Russia, punishable by imprisonment, loss of all rights, banishment to the provinces or exile from Russia altogether; therefore, Tchaikovsky's fear of social rejection was grounded in some justification. Musicologist Solomon Volkov mentions state do

ents that indicate men attracted to the same sex "were under tight police surveillance" and maintains that public life in Russia was "based not on laws but on 'understandings.' That means that formally existing laws are applied or ignored based on the position and wishes of the authorities.... No one could feel confident of the future in those conditions (which is one of the goals of a society built on 'understandings')." The other argument is that the Imperial bureaucracy was considerably less draconian in Tchaikovsky's lifetime than previously imagined. Russian society, with its surface veneer of Victorian propriety, may have been no less tolerant than the government. In the introduction to a French edition of her biography of Tchaikovsky (first published in Russian in 1936 and reissued in French in 1987) Nina Berberova cites many cir

ents that indicate men attracted to the same sex "were under tight police surveillance" and maintains that public life in Russia was "based not on laws but on 'understandings.' That means that formally existing laws are applied or ignored based on the position and wishes of the authorities.... No one could feel confident of the future in those conditions (which is one of the goals of a society built on 'understandings')." The other argument is that the Imperial bureaucracy was considerably less draconian in Tchaikovsky's lifetime than previously imagined. Russian society, with its surface veneer of Victorian propriety, may have been no less tolerant than the government. In the introduction to a French edition of her biography of Tchaikovsky (first published in Russian in 1936 and reissued in French in 1987) Nina Berberova cites many cir stances that confirm social visibility and impunity of homosexual men in 1890s Russia.

stances that confirm social visibility and impunity of homosexual men in 1890s Russia.In any case, Tchaikovsky chose not to neglect social convention and stayed conservative by nature. His love life remained complicated. A combination of upbringing, timidity and deep commitment to relatives precluded his living openly with a male lover. A similar blend of personal inclination and period decorum kept him from having sexual relations with those in his social circle. He regularly sought out anonymous encounters, many of which he reported to Modest; at times, these brought feelings of remorse. He also attempted to be discreet and adjust his tastes to the conventions of Russian society. Nevertheless, many of his colleagues, especially those closest to him, may have either known or guessed his true sexual nature. Tchaikovsky's decision to enter into a heterosexual union and try to lead a double life was prompted by several factors—the possibility of exposure, the willingness to please his father, his own desire for a permanent home and his love of children and family. There is no reason however to suppose that these personal travails impacted negatively on the quality of his musical inspiration or capacity. An upcoming Russian film, Tchaikovsky, has attracted controversy due to the fact that Tchaikovsky's sexuality, mentioned in early drafts, has been written out of the film in order to secure funding from the Russian government.

Death

On 28 October 1893 Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique In Saint Petersburg. Nine days later, Tchaikovsky died there, aged 53. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka, and Modest Mussorgsky; later, Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev were also buried nearby.

While Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier, some have theorized that his death was a suicide. Opinion has been summarized as follows: "The polemics over [Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumor attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out ....."

_1464_68_0.jpg)

-St Sebastian Tended by St Irene--2 copy_0.jpg)