How Boxers and Briefs Got Into Men's Pants

Jockeying for Position: How Boxers and Briefs Got Into Men's Pants

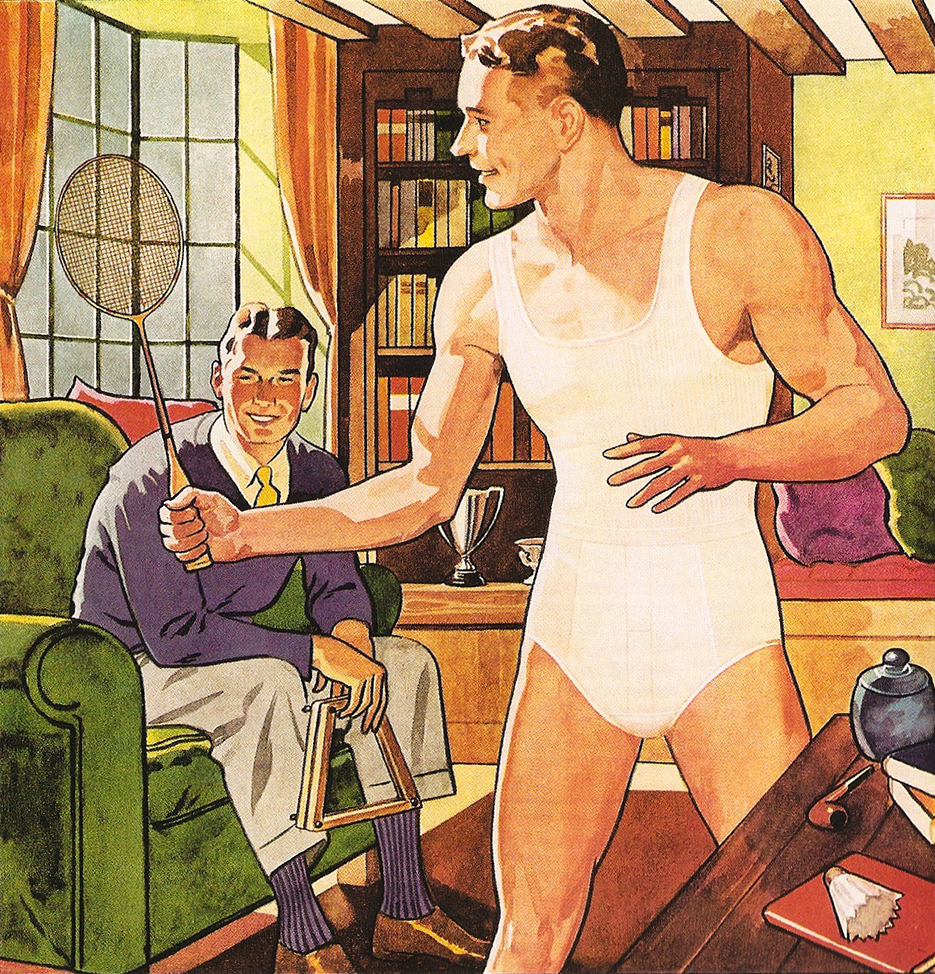

Above: Underwear is portrayed as essential to the sporting life, in a 1930s ad for “Skit-Suits.

Just as underclothes are shielded from public view, the evolution of men’s most intimate apparel is shrouded in secrecy. But the story of men’s underwear is about more than which came first, boxers or briefs. Undergarments as we know them today were first sold to promote cleanliness and improve the comfort of wearing clothing. That they might one day be deemed fashionable was not even an after-thought.

“Shirts were regarded as a form of underwear until the early 1920s.”

In particular, in the 19th century, men’s underwear was closely linked with hygiene; associating these undergarments with athleticism, let alone sexuality, is a 20th-century notion. These shifts paralleled a growing public acceptance of the undressed male body, moving from the chaste forms of the Victorian era to the endlessly scrutinized torsos of today.

As a researcher and lecturer on fashion history and curation at the London College of Fashion, Shaun Cole knows a lot about undies. Cole has conducted extensive research on the evolution of men’s clothing, focusing on the way menswear expresses masculinity and sexual identity. Naturally, this focus led Cole to undergarments, the type of apparel most closely connected with physical desire and, um, manhood.

In 2007, Parkstone Press published Cole’s “The Story of Men’s Underwear,” which explores the historical arc of undergarments, and Cole is currently co-editing a book titled “Fashion Media: Past and Present,” which includes an essay on male underwear marketing. Recently, we spoke with Cole about the hidden history of drawers, jockeys, skivvies, boxers, and briefs.

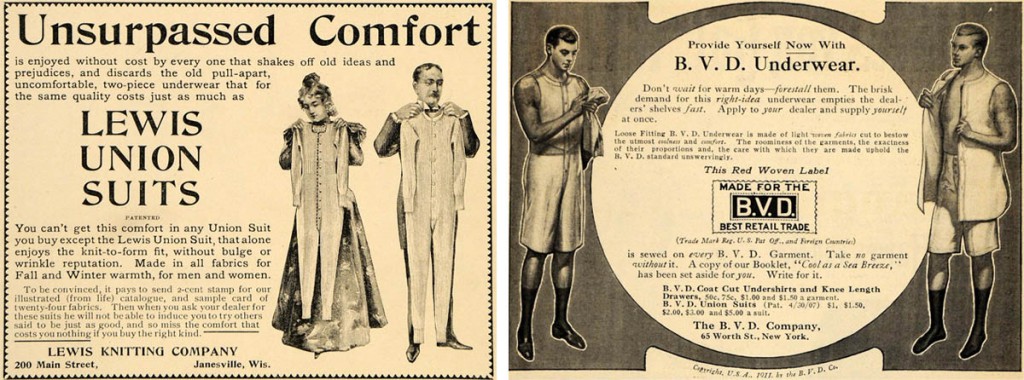

Above left: An 1897 Lewis Union Suits ad displays underclothes in the socially accepted manner. Above right: This B.V.D. ad includes a risque display of male chest, circa 1911.

Collectors Weekly: When did most men begin wearing underwear?

Shaun Cole: Some of the earliest examples are the loin cloth type of undergarment worn by Ötzi, the frozen man found in the Swiss Alps, as well as the loin cloths found in Tutankhamen’s tomb. And if you look at medieval and Renaissance paintings, you can often see a layer of clothing underneath the outer layer.

By the mid-19th century, we had started to develop a commercial industry creating underwear. But the standardization of underwear didn’t happen until the late 19th century, when it became common for men from all levels of society to wear undergarments. At the time, underwear tended to be sold through retailers that were also selling other garments, such as shirts, which were regarded as a form of underwear until the early 1920s.

Collectors Weekly: Was underwear openly advertised?

Cole: Certainly by the 1880s, there were advertisements, and by the 20th century, there were masses of adverts. The earliest ones tend to be quite text-based, but that was common with all advertising of that era. When you started to see images being included, there were a number of companies using classical statues with undergarments superimposed over them, or dressed people holding underwear up in front of them to avoid this public negotiation with a semi-clothed or naked body. However, by 1907, for example, B.V.D. was advertising its coat-cut undershirts, which are shown open in illustrations so you can actually see the man’s chest.

Above: The athletic association of underwear started around 1900, as shown in this Munsingwear ad from the era.

Most brands, like Wright’s and Dr. Jaeger’s, were going with the idea that underwear was hygienic, allowing your body to breathe. The concept of cleanliness appeared quite often in adverts specifically targeted towards female consumers, the wives and sisters and mothers, though the language was often about ease of cleaning the garments. But you also started to get this idea of comfort as well, how a man should be comfortable in his underwear.

By the 1950s, advertising imagery of underwear was everywhere. You still had the hygienic element to some extent, but there was a move in American advertising toward this idea of the family man. It was a postwar, McCarthy-influenced idea about the role of the man as the father and the head of the family. Often, there was a sort of sporting element in there, with fathers and sons playing basketball or boxing or those kinds of things. There was a lot of sporting imagery in underwear. Of course, it wasn’t just about promoting a sporty body: It was a justification for presenting a man semi-clothed, a legitimate means of looking at a man.

Collectors Weekly: Did underwear have its own break-out moment?

Cole: The 1920s and 1930s started to see a change with the rise in athleticism and sportiness. In the 1934 film “It Happened One Night,” Clark Gable is shown taking off his shirt, and he is bare-chested. This was the first time a man in a domestic scenario was shown bare-chested. The cultural mythology has it—although there’s no proof of this—that sales of undershirts reduced drastically at that point.

Most brands, like Wright’s and Dr. Jaeger’s, were going with the idea that underwear was hygienic, allowing your body to breathe. The concept of cleanliness appeared quite often in adverts specifically targeted towards female consumers, the wives and sisters and mothers, though the language was often about ease of cleaning the garments. But you also started to get this idea of comfort as well, how a man should be comfortable in his underwear.

By the 1950s, advertising imagery of underwear was everywhere. You still had the hygienic element to some extent, but there was a move in American advertising toward this idea of the family man. It was a postwar, McCarthy-influenced idea about the role of the man as the father and the head of the family. Often, there was a sort of sporting element in there, with fathers and sons playing basketball or boxing or those kinds of things. There was a lot of sporting imagery in underwear. Of course, it wasn’t just about promoting a sporty body: It was a justification for presenting a man semi-clothed, a legitimate means of looking at a man.

Collectors Weekly: Did underwear have its own break-out moment?

Cole: The 1920s and 1930s started to see a change with the rise in athleticism and sportiness. In the 1934 film “It Happened One Night,” Clark Gable is shown taking off his shirt, and he is bare-chested. This was the first time a man in a domestic scenario was shown bare-chested. The cultural mythology has it—although there’s no proof of this—that sales of undershirts reduced drastically at that point.

A shirtless Clark Gable in 1934’s “It Happened One Night” signified the changing norms for male nudity.

In the postwar period, with the introduction of youth fashion and tighter, closer-fitting, teenage subcultural styles, as well as central heating, people began to want undergarments less. It had really been about keeping warm, all the layering up. So things like T-shirts, which were initially undershirts, started to be worn as outer garments.

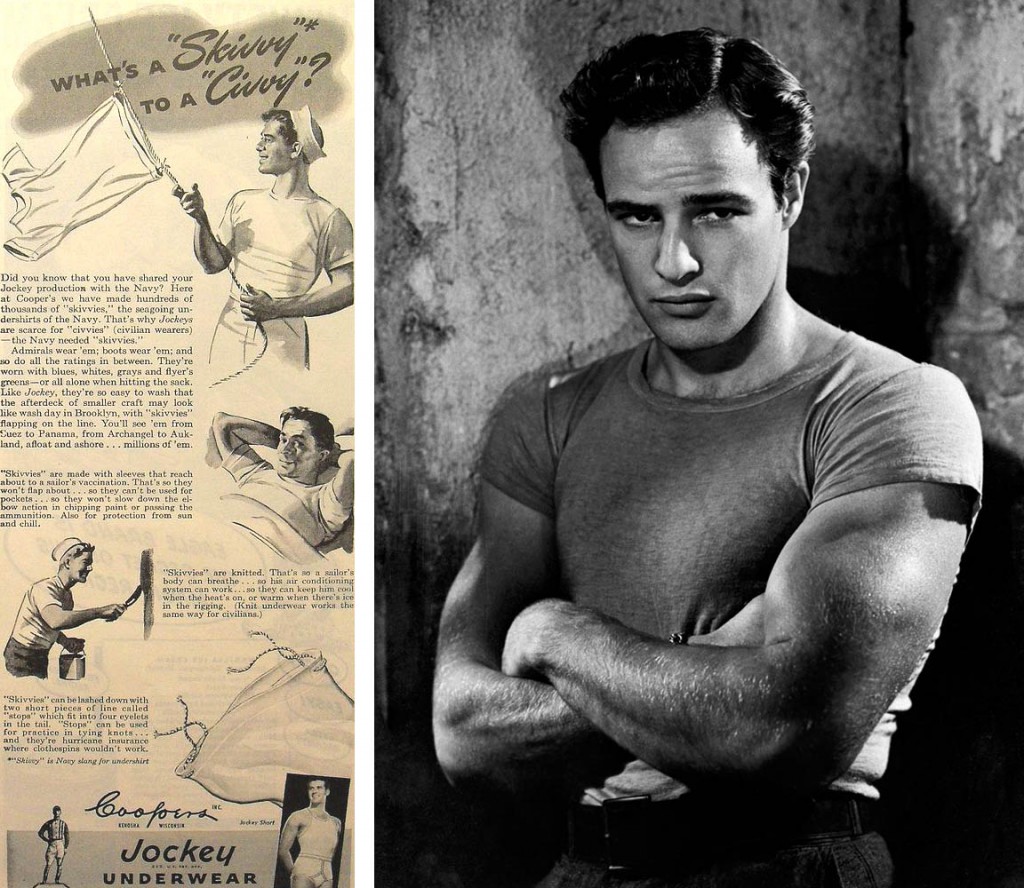

Historically, the T-shirt was a military garment, a naval garment, in fact. By the Second World War, cotton started to take over from wool for the construction of those undergarments. Soldiers and sailors coming back from war, having been issued these short-sleeved cotton shirts in the military, started to wear them as part of their civvy clothing. And in fact, some of the advertising in the 1930s and ’40s—I think it was Sears & Roebuck—actually referred to them “training shirts” or “gob shirts” or “army-style T-shirts.”

Above left: A Jockey underwear ad from the 1940s highlights the military origins of T-shirts. Above right: Marlon Brando epitomized the rebellious T-shirt contingent in 1951’s “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

So they went from being specifically an undershirt to being an outer garment, representing a transgressive act by teenage men. They were very much associated with the idea of the rebel, particularly through people like Marlon Brando and James Dean.

Collectors Weekly: When did it become legal for men to go shirtless in public?

Cole: It varied from country to country, but in America, I think the laws changed in the 1930s. The popularity of actors like Johnny Weissmuller, who was a sporting legend and then played Tarzan, led to a change of thought around the presentation of the male body, and it became much more acceptable.

“Suddenly, men were presented for sale as women had been.”

If you look at advertising for swimwear, by the late ’30s it was acceptable for non-working classes to get a suntan. Leisure became about lounging shirtless on the beach. There was a huge change in attitudes pre- and postwar.

Collectors Weekly: Did elastic waistbands have an effect on this as well?

Cole: Certainly. Even though elastic was invented in the late 19th century, by the 1930s, it was much more common. Coopers, with their jockey Y-fronts, introduced Lastex into its underwear at that point. You started to see the notion of underwear being comfortable and supportive of the male physique, rather than hygienic. Adding elastic waistbands meant that you didn’t have the bulkiness of ties or buttons or side buckles on your underwear; they became self-supporting.

Then, in the ’50s and ’60s, new manmade fibers started to be introduced. This began a little in the 1930s, with materials like rayon, but by the 1950s, nylon and polyester and other manmade fibers were definitely being used much more.

Collectors Weekly: When did briefs really enter the picture?

Cole: The first advertisement I’m aware of for briefs is a French advert from 1913 from the magazine L’Illustration. It’s for a “slip,” which translates as brief. I can’t remember the exact wording, but it does say for support in sporting activity.

Above left: This French brand Kangourou was one of the first to offer “slips,” also known as briefs in America Above right: Superman’s costume was revealing but modest at the same time.

Coopers also used the term jockey for its Y-front briefs to allude back to the jock strap or athletic supporter, which was initially introduced for cyclists in Boston in the 1870s. While it might not have been directly about sporting underwear, it certainly suggested the healthy, sporty man.

Superman first appeared in 1938, three years after Jockey launched its briefs. In order to make him acceptable, Superman had to be wearing some kind of full body-covering garment. It was about showing off his heroic, muscular body, which you could trace back to classical sculpture, but he couldn’t be shown naked or semi-clad. But if you think about the fact that his briefs have a belt on them, they are much more aligned to swimwear design than they are to underwear.

Collectors Weekly: How did Calvin Klein revolutionize the standard white brief?

Cole: Interestingly, Calvin Klein’s first range of underwear in the 1980s was made in the same factories as Jockey. Even though we think that Calvin Klein invented this idea of the brand name in the waistband, Jockey was doing that in the 1950s. But what Klein did was to make the rise slightly lower, to make the fit slightly tighter. He also tried out his prototypes himself. He reputedly took a number of styles with him to Fire Island and tried them out to find which one fitted the best.

Calvin Klein's very first underwear campaign in 1982 featured pole vaulter Tom Hintaus as photographed by Bruce Weber.

Calvin Klein’s very first underwear campaign in 1982 featured pole vaulter Tom Hintaus as photographed by Bruce Weber.

And it wasn’t just his garment, it was the way he advertised those garments as well, which had a huge impact. The advertising campaign had around a $500,000 budget for the launch of his underwear. Klein was much more conscious of the male form underneath those garments than other designers, so he introduced this element of sex appeal. I’m not saying this wasn’t in underwear previously, but it was definitely a very underground thing, not for mainstream underwear. Klein presented that to the mainstream. He effectively made underwear sexy.

Through the 1970s, you had this explosion of color and pattern, but Klein went back to a classic simplicity that was reflected in the form of the man in the advertising. So you had this statuesque, athletic body in a very classic, simple, white garment. The question, really, is about what was being sold: Suddenly, men were presented for sale in the way that women had been in advertising. One of Calvin Klein’s biggest impacts wasn’t on underwear but on the presentation of men in popular culture.