Are We Living Inside A Black Hole?

Are We Living In A Black Hole?

National Geographic | By Michael Finkel | February 19, 2014

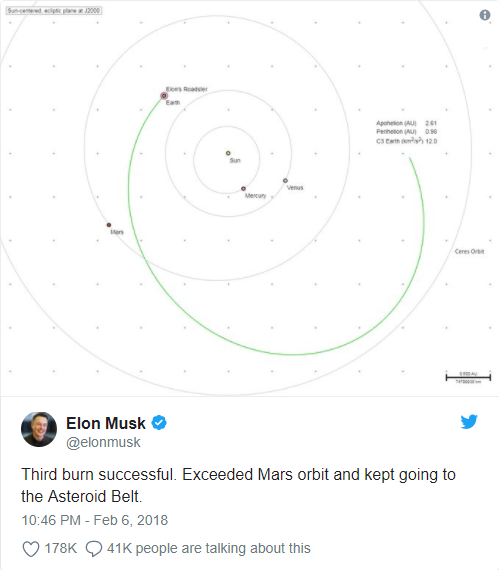

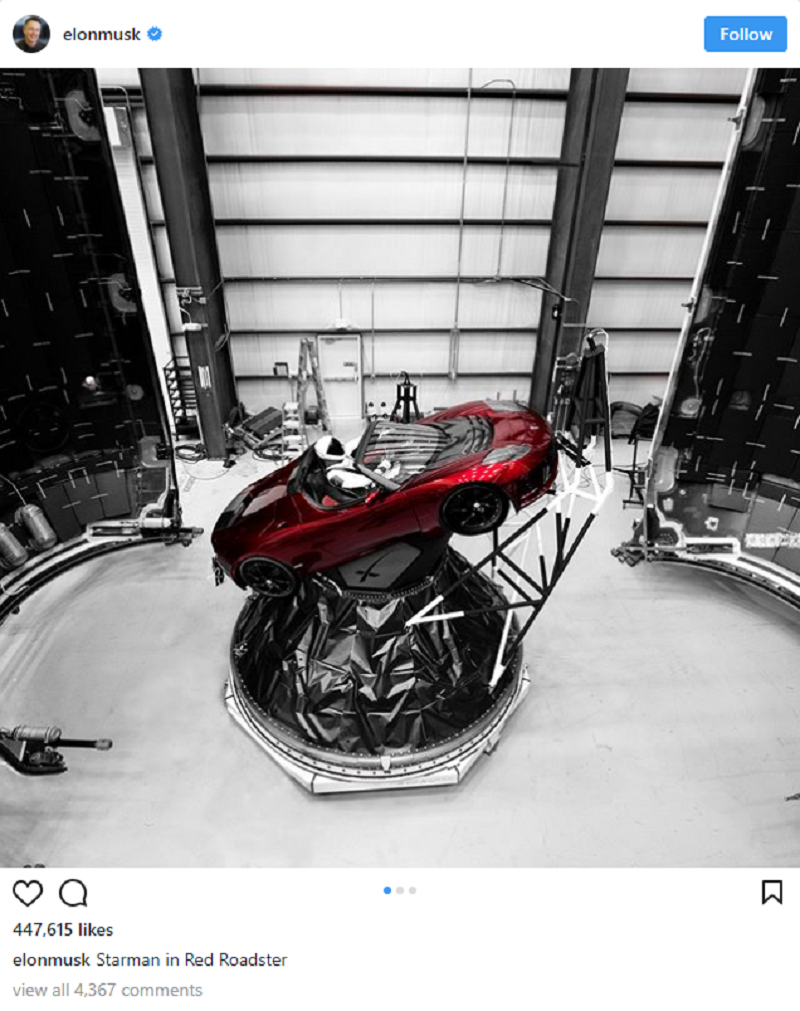

A surprising spiral shape in the nearby active galaxy NGC 1433, shown above, indicates material flowing in to fuel a black hole. A jet of material flowing away from the black hole has also been observed.

Let's rewind the clock. Before humans existed, before Earth formed, before the sun ignited, before galaxies arose, before light could even shine, there was the Big Bang. This happened 13.8 billion years ago.

But what about before that? Many physicists say there is no before that. Time began ticking, they insist, at the instant of the Big Bang, and pondering anything earlier isn't in the realm of science. We'll never understand what pre-Big Bang reality was like, or what it was formed of, or why it exploded to create our universe. Such notions are beyond human understanding.

But a few unconventional scientists disagree. These physicists theorize that, a moment before the Big Bang, all the mass and energy of the nascent universe was compacted into an incredibly dense—yet finite—speck. Let's call it the seed of a new universe. (See also: "Origins of the Universe.")

This seed is thought to have been almost unimaginably tiny, possibly trillions of times smaller than any particle humans have been able to observe. And yet it's a particle that can spark the production of every other particle, not to mention every galaxy, solar system, planet, and person.

If you really want to call something the God particle, this seed seems an ideal fit.

So how is such a seed created? One idea, bandied about for several years—notably by Nikodem Poplawski of the University of New Haven—is that the seed of our universe was forged in the ultimate kiln, likely the most extreme environment in all of nature: inside a black hole. (See "Star Eater" in this month's National Geographic magazine.)

Multiverses Multiply

It's important to know, before we go further, that over the last couple of decades, many theoretical physicists have come to believe that our universe is not the only one. Instead, we may be part of the multiverse, an immense array of separate universes, each its own shining orb in the true night sky.

How, or even if, one universe is linked to another is a source of much debate, all of it highly speculative and, as of now, completely unprovable. But one compelling idea is that the seed of a universe is similar to the seed of a plant: It's a chunk of essential material, tightly compressed, hidden inside a protective shell.

This precisely describes what is created inside a black hole. Black holes are the corpses of giant stars. When such a star runs out of fuel, its core collapses inward. Gravity pulls everything into an increasingly fierce grip. Temperatures reach 100 billion degrees. Atoms are smashed. Electrons are shredded. Those pieces are further crumpled.

The star, by this point, has turned into a black hole, which means that its gravitational pull is so severe that not even a beam of light can escape. The boundary between the interior and exterior of a black hole is called the event horizon. Enormous black holes, some of them millions of times more massive than the sun, have been discovered at the center of nearly every galaxy, including our own Milky Way.

Bottomless Questions

If you use Einstein's theories to determine what occurs at the bottom of a black hole, you'll calculate a spot that is infinitely dense and infinitely small: a hypothetical concept called a singularity. But infinities aren't typically found in nature. The disconnect lies with Einstein's theories, which provide wonderful calculations for most of the cosmos, but tend to break down in the face of enormous forces, such as those inside a black hole—or present at the birth of our universe.

Physicists like Dr. Poplawski say that the matter inside a black hole does reach a point where it can be crushed no further. This "seed" might be incredibly tiny, with the weight of a billion suns, but unlike a singularity, it is real.

The compacting process halts, according to Dr. Poplawski, because black holes spin. They spin extremely rapidly, possibly close to the speed of light. And this spin endows the compacted seed with a huge amount of torsion. It's not just small and heavy; it's also twisted and compressed, like one of those jokey spring-loaded snakes in a can.

Which can suddenly unspring, with a bang. Make that a Big Bang—or what Dr. Poplawski prefers to call "the big bounce."

It's possible, in other words, that a black hole is a conduit—a "one-way door," says Dr. Poplawski—between two universes. This means that if you tumble into the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, it's conceivable that you (or at least the shredded particles that were once you) will end up in another universe. This other universe isn't inside ours, adds Dr. Poplawski; the hole is merely the link, like a shared root that connects two aspen trees.

And what about all of us, here in our own universe? We might be the product of another, older universe. Call it our mother universe. The seed this mother universe forged inside a black hole may have had its big bounce 13.8 billion years ago, and even though our universe has been rapidly expanding ever since, we could still be hidden behind a black hole's event horizon.

venting gravitational machinations. And it just might turn out to be a brilliant way to "solve" quantum gravity. But as of right now, there are a few catches. For one, we don't live in an anti-de Sitter universe. Our universe is full of matter, radiation and dark energy, and has almost perfectly flat geometry. Is there a similar correspondence that works in our real universe? Perhaps, and theorists are working hard to find it.

venting gravitational machinations. And it just might turn out to be a brilliant way to "solve" quantum gravity. But as of right now, there are a few catches. For one, we don't live in an anti-de Sitter universe. Our universe is full of matter, radiation and dark energy, and has almost perfectly flat geometry. Is there a similar correspondence that works in our real universe? Perhaps, and theorists are working hard to find it.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58527923/DU6DAbgUMAAWbNZ__1_.0.jpg)

:origin()/pre00/164d/th/pre/i/2016/045/9/a/poster__heavy_metal_by_adripan-d9roy6a.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fblueprint-api-production.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fuploads%2Fcard%2Fimage%2F708634%2F4c179890-8091-46d5-9704-f25c92cc5e4d.jpg)